Cheers

Hook and Norton - Haymaker

- Wonkydonkey

- Drunk as a Skunk

- Posts: 847

- Joined: Sat Mar 01, 2014 9:37 am

- Location: In the Stables

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

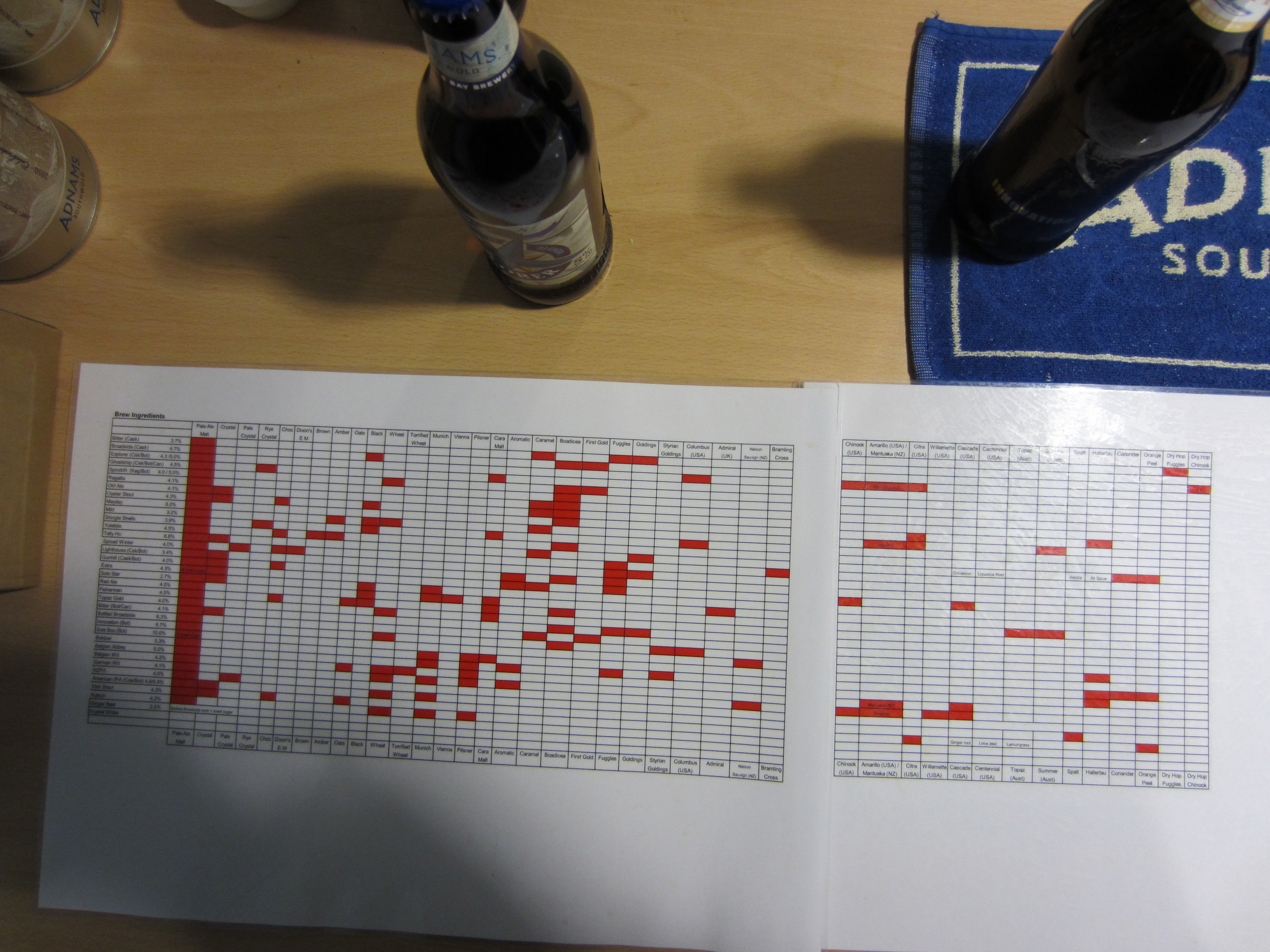

Can we see the adnams chart in a readable pic, the writing is unreadable when enlarged.

Cheers

Cheers

To Busy To Add,

- seymour

- It's definitely Lock In Time

- Posts: 6390

- Joined: Wed Jun 06, 2012 6:51 pm

- Location: Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA

- Contact:

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

Okay, let's try flickr links instead:Wonkydonkey wrote:Can we see the adnams chart in a readable pic, the writing is unreadable when enlarged.

Cheers

https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/326/31651 ... ae7a_o.jpg

https://c1.staticflickr.com/1/442/31651 ... 0b39_o.jpg

- Eric

- Even further under the Table

- Posts: 2920

- Joined: Fri Mar 13, 2009 1:18 am

- Location: Sunderland.

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

With total confidence I'll say that Dixon's EM inclusion has absolutely no involvement in liquor treatment or mash pH adjustment in the brewing of Adnams Spiced Winter Beer.

Without patience, life becomes difficult and the sooner it's finished, the better.

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

GW had a post on Dixons EM when he was posting here, I can't find it though after a brief search

- Eric

- Even further under the Table

- Posts: 2920

- Joined: Fri Mar 13, 2009 1:18 am

- Location: Sunderland.

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

Might this be that post? I see you participated.Hanglow wrote:GW had a post on Dixons EM when he was posting here, I can't find it though after a brief search

Acid malt is normally used for between 3 and 5% of grist and can reduce mash pH by 0.1 to 0.25. For water like mine that would result in a mash pH of 5.8 at best without other treatment and to use more would give the beer a distict lactic flavour which is possibly the reason Adnams used that malt in that particular beer and not in any other.

Organic acids like lactic (phosphoric, citric, acetic are amongst others) produce significant buffering capacity when used in a mash to achieve a specific pH to produce a wort that frequently needs further acidification in order for pH to be of the right order in subsequent processes. This might be common in lager production, but as far as I know not in any way something that could be suggested as commonplace for traditional British style ales.

Without patience, life becomes difficult and the sooner it's finished, the better.

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

Yeah I'd read his post a while before that and was clearly able to find it in search to quote it but can't now for some reason

Unless he posted it on another message board and that's where I got the quote from

edit: ok that was annoying me so google turned up his comment on rons site for a lees beer

http://barclayperkins.blogspot.co.uk/20 ... c-ale.html

Unless he posted it on another message board and that's where I got the quote from

edit: ok that was annoying me so google turned up his comment on rons site for a lees beer

http://barclayperkins.blogspot.co.uk/20 ... c-ale.html

- seymour

- It's definitely Lock In Time

- Posts: 6390

- Joined: Wed Jun 06, 2012 6:51 pm

- Location: Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA

- Contact:

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

orlando wrote:...I use Hydrochloric acid for this as I want to reverse my "flavour" Ions to favour chloride rather than the sulphate bias I am looking for in my Pales. I am unaware of acid "denaturing" you suggest so that is still a comment I am perplexed by.

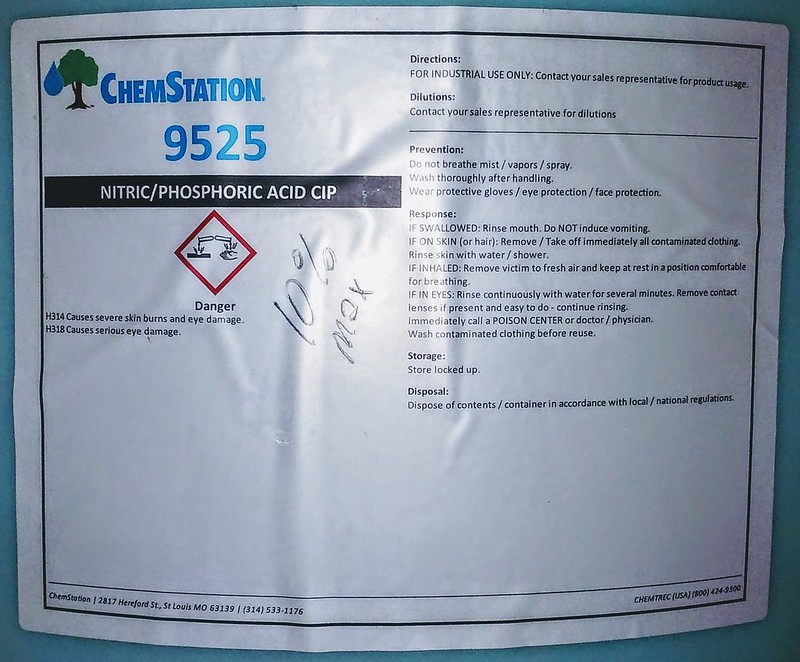

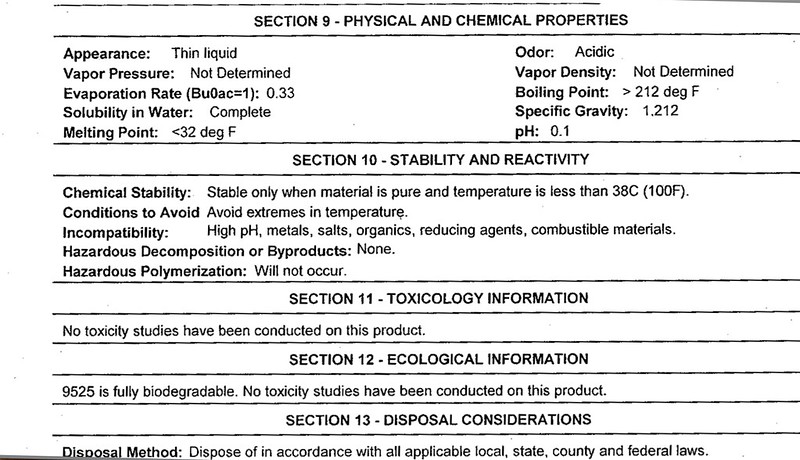

This is the Nitric/Phosphoric acid we keep in bulk for when we CIP (clean in place) tanks. We also use a little when counting yeast, when it's a super clumpy strain like Fullers, as well as a few other odd jobs around the brewery. I haven't personally researched ideal temperature ranges for your hydrochloric acid, but as you can see, ours is only stable below 100°F, which makes it incompatible in our 180°F hot liquor tank, as well as in our 167°F sparge water (to achieve a 150°F overall mash temp.) Surely there are other acids we could try those ways, but we've got a system which works well for us: minimal calcium and sodium treatment in the hot liquor tank, plus varying (small) percentages of acid malt in our pale grainbills. As I've said, I believe some English breweries probably do similarly, even on traditional English ales. Meanwhile, you've clearly arrived at another equally effective "way to skin the cat."

Anyway, I apologize for this lengthy distraction from the original Hook Norton Haymaker post...

- seymour

- It's definitely Lock In Time

- Posts: 6390

- Joined: Wed Jun 06, 2012 6:51 pm

- Location: Los Alamos, New Mexico, USA

- Contact:

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

I'm not arguing, just curious why you would say that? I can report from experience that even small percentages of acidulated malt in the grainbill most certainly affect mash pH, even if the intended purpose was flavour.Eric wrote:With total confidence I'll say that Dixon's EM inclusion has absolutely no involvement in liquor treatment or mash pH adjustment in the brewing of Adnams Spiced Winter Beer.

- orlando

- So far gone I'm on the way back again!

- Posts: 7201

- Joined: Thu Nov 17, 2011 3:22 pm

- Location: North Norfolk: Nearest breweries All Day Brewery, Salle. Panther, Reepham. Yetman's, Holt

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

seymour wrote:

This is the Nitric/Phosphoric acid we keep in bulk for when we CIP (clean in place) tanks.

These are two unrelated acids to the ones I use and they are being used as essentially a cleaning product. On the issue of thermal stability for Hydrochloric acid my research has come up with this:

Hydrochloric acid has high thermal stability.

Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. 3rd ed., Volumes 1-26. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, 1978-1984., p. 12(80) 984

I am "The Little Red Brooster"

Fermenting:

Conditioning:

Drinking: Southwold Again,

Up Next: John Barleycorn (Barley Wine)

Planning: Winter drinking Beer

Fermenting:

Conditioning:

Drinking: Southwold Again,

Up Next: John Barleycorn (Barley Wine)

Planning: Winter drinking Beer

- Eric

- Even further under the Table

- Posts: 2920

- Joined: Fri Mar 13, 2009 1:18 am

- Location: Sunderland.

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

That was partially explained in my subsequent posting, but to avoid misconception could mean examining a lot of chemistry, brewing history including politics and the water used by every major brewery. A book might do the subject justice, but could be so controvertial that a British author might risk extradition to the US on Trumped up charges.seymour wrote:I'm not arguing, just curious why you would say that? I can report from experience that even small percentages of acidulated malt in the grainbill most certainly affect mash pH, even if the intended purpose was flavour.Eric wrote:With total confidence I'll say that Dixon's EM inclusion has absolutely no involvement in liquor treatment or mash pH adjustment in the brewing of Adnams Spiced Winter Beer.

In earlier days of brewing, ingredients would be obtained locally. In time, better and cheaper alternatives would be sought from further afield, but water was expensive to transport. Even so, in the 19th century, when its influence was know but not well understood, water was transported by rail from Burton to other English breweries and some of the more wealthy London brewers opened new premises in Burton for that water. Now while some, particularly those west of the Atlantic, insist Burton Brewers did things to avoid using that water as was, it is patently obvious it was that water's properties that gave this beer its fame and the resultant demand. Similarly in Tadcaster, Roman name Calcaria from the Latin for lime, second to Burton for beer production has water different to Burton, but both contain significantly more calcium, magnesium and sulphates than most other waters in this sceptered isle. My home is on the same magnesian limestone as Tadcaster, remnanats of the rim of the Zechstein Sea before it dried up. My water supply is similar to the majority of the population of Great Britain, it is hard and alkaline.

Large areas of Great Britain have soft water, all of Northern Scotland, North West and South West of England as well as parts of Wales and other small areas as well as those with water from such areas. Here were breweries too, but while many made decent beer, few received the acclaim or demand that those located in hard water areas did and most of those would likely have their own wells.

London with its large population's immense demand for beer is a bit of an enigma and I suspect their beer varied greatly in quality. Using water from the Thames was restricted from Elizabethan times and quality from early wells in London Clay and the chalk beneath only can now be a matter of opinion. A recent paper published in the US on the web advised water extracted from London chalk contained little calcium, and while ion exchange varies with depth and oxygen content, the figures quoted were more the exception than the rule, lower than the actual measurements I have from successful London breweries. Also, Meux Brewery, that famous for the flood in 1814 when more than a quarter of a million gallons of porter burst fom a vat, was but one brewery to bore through the chalk into green sand and obtain water like the rest of the South East with decent level of calcium and less sodium. Even so, Burton's output would soon be ready to overtake London's and why could that be when London had access to every ingredient Burton used, except the water unless, of course, they went to the extent of importing it?

My water mostly has alkalinity of 255mg/l as calcium carbonate, but it varies depending upon how much rain we've had. The rain dilutes the supply and the relationship between major ions is for all practical purposes constant. This means by a swift and simple TDS measurement I can accurately assess the quantity of each of the major ions and equally swiftly (10 minutes maximum) adjust them to suit for the beer being brewed. A couple of years ago I did some tests the results I'll use here.

All pale malt mashed with my water when its alkalinity was 150mg/l as CaCO3 produced a pH reading of 6.23 after 12 minutes. That level of alkalinity is not uncommon in this country. If 5% of that malt was replaced by acid malt the resulting pH could be expected to be 0.25 less, but still almost 6.0. Now one might be forgiven for thinking another 5% would see pH below 5.75, but while one would be forgiven, one would be incorrect, the reading more likely to be closer to 5.9. The more lactic acid added, the lesser would be the the reduction in pH such that it may not even be possible to achieve a good mash pH.

Another all pale malt mash was done with the same water but treated with mineral acid for alkalinity of 87.5mg/l as CaCO3. Mash pH was 5.87 after 12 minutes.

A third all pale mash with alkalinity further reduced with the same mineral acid to 25mg/l had a mash pH of 5.52 afer 12 minutes.

Now the same amount of mineral acid to drop alkalinity from 150 to 87.5 will be needed for 87.5 to 25mg/l as CaCO3 and will likely be similar (although I don't know for certain) when using an organic one like lactic acid, the difference is due to the chemicals produced in the reaction. Using sulphuric acid the alkalinity is turned into sulphate and by hydrochloric acid into a chloride, neither of which have substantial buffering capacity where as lactic acid does and accordingly it's influence isn't linear.

Phosphoric is another, an acid that has little practical value to brewers with very alkaline water apart from washing yeast and cleaning metal. It will reduce alkalinity, one third of the acid does, but two thirds remains in solution to act as a strong buffer stopping pH falling at the normal rate, the traditional rate, the anticipated rate to that British beers need to supports healthy traditional conditioning in a cask. Maybe should America adopt casking and hand pumps they might find a final beer pH of about 4.0 is what is needed, and that pH 4.6 isn't.

Lots in Britain found reducing alkalinity with phosphoric acid left significant calcium deposits on the bottom of our HLTs that proved difficult to remove. I think Martin Brungard made a very profound statement in a recent post defending this which I've totally failed to locate. He said that if calcium was deposited when using phosphoric the water contained too much calcium. But if one were to look at that statement as one would a mathematical equation to rearrange the operators coefficients and variables it is possible to produce an alternative statement, that phosphoric acid can be suitable for adjusting alkalinity in brewing liquor when it does not deposit calcium.

I think the brewing liquor at Adnams might well contain more than 200mg/l of alkalinity as CaCO3. Orlando will know better, he lives much closer to that brewery with the possibility of having very similar water to theirs. Alkalinity needs to be at its least for all pale malt mashes. Only one brew uses acid malt and there are some of all pale malt. That brew is a spiced brew, one with the least beer like taste of them all. The acid malt will have some influence on mash ph, but it's my opinion that any influence would be negated by the subsequent buffering by the residual components from that reaction unless Adnams had some reason to produce a beer with a pH higher than is usual in UK.

Without patience, life becomes difficult and the sooner it's finished, the better.

- orlando

- So far gone I'm on the way back again!

- Posts: 7201

- Joined: Thu Nov 17, 2011 3:22 pm

- Location: North Norfolk: Nearest breweries All Day Brewery, Salle. Panther, Reepham. Yetman's, Holt

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

Before I properly understood my water and British brewing techniques I followed Martin's advice and used Phosphoric acid. I noticed that my HLT liquour was leaving behind a huge amount of precipitate that I now understand contains calcium. The major reason for swapping to sulphuric and hydrochloric because although I start with a healthy 144 experiments followed by chemical analysis by a lab showed almost 1/2 is lost in the mash using sulphuric acid, I suspect that even more is lost using phosphoric as my HLT liquour does not look like this these days.Eric wrote: Lots in Britain found reducing alkalinity with phosphoric acid left significant calcium deposits on the bottom of our HLTs that proved difficult to remove. I think Martin Brungard made a very profound statement in a recent post defending this which I've totally failed to locate. He said that if calcium was deposited when using phosphoric the water contained too much calcium. But if one were to look at that statement as one would a mathematical equation to rearrange the operators coefficients and variables it is possible to produce an alternative statement, that phosphoric acid can be suitable for adjusting alkalinity in brewing liquor when it does not deposit calcium.

I think the brewing liquor at Adnams might well contain more than 200mg/l of alkalinity as CaCO3. Orlando will know better, he lives much closer to that brewery with the possibility of having very similar water to theirs.

My alkalinity is circa 250, I can't remember what Adnams is but suspect Eric is right in it being north of 200. I do know they adjust it but not using acidulated or enzymic malt.

I am "The Little Red Brooster"

Fermenting:

Conditioning:

Drinking: Southwold Again,

Up Next: John Barleycorn (Barley Wine)

Planning: Winter drinking Beer

Fermenting:

Conditioning:

Drinking: Southwold Again,

Up Next: John Barleycorn (Barley Wine)

Planning: Winter drinking Beer

Re: Hook and Norton - Haymaker

I started homebrewing (finally) in January. After a few batches I wanted to try something along the lines of a refreshing pale ale as the weather warms up (I'm British but living in Texas, and March has been a warm month so far). I've always been a fan of Hook Norton beers and this thread was one of the few places I could find info on Haymaker. I cobbled together a recipe loosely based on bits and pieces from here . . . more of a jab than a haymaker.

Hooky Haymaker v1

For 10 L in fermentor, BIAB.

Treated mash tun water (tap water) with ~3 g gypsum and ~1 g calcium chloride. All water (~14 L) was treated with a Campden tablet.

Mashed in 9.5 L @ 66°C for 2 hours. Dunk sparged in 4.5 L @ ~69°C for 15 minutes.

About 12 L in boil kettle, 60 minute boil.

OG: 1.052 (Actual OG: 1.053)

FG: 1.014 (Actual FG: 1.012)

ABV: 5% (Calc. ABV: 5.4%)

Atten.: 72% (Actual att.: 77%)

IBU: 40 (Calc. IBUs: 44–46%)

GRAIN BILL (kg)

1.95 91.1% Maris Otter

0.11 5.1% Carapils (1.7–2.4°L)

0.08 3.7% acidulated malt

Total

2.14 100.0%

HOP SCHEDULE (pellets, in grammes)

12 @ 60 min. Challenger (7.8% AA)

8 @ 30 min. Challenger (7.8% AA)

5.5 @ 30 min. Fuggle (5.3% AA)

30 @ 5 min. Styrian Golding Celeia (2.6% AA)

YEAST

WY1318 London Ale III, pitched @ 22°C, fermented ~18°C for 5 days then allowed to rise to 23°C for ten days (so far).

The Wyeast 1318 harvested from a previous batch, kept in fridge under its beer. Made a 400 mL ‘shaken not stirred’ starter, which had been going for 24 hours by the time I pitched it into the Hooky Haymaker. Pitched into ~22°C wort, then moved carboy to a water bath and kept it between 17 and 19°C for about five and a half days, then moved it to a dark closet. The beer has hovered around 22–23°C thereafter.

It's been in the primary for fifteen days now and took a gravity reading this morning (1.012 SG). I’m really pleased with how it tastes so far. The hydrometer sample’s initial taste had some lovely citrus lemon notes and a subtle bitterness that blends with a slight malt and ester finish. Beer is light but also smooth feeling rather than thin (it’s obviously uncarbonated at this point).

I’m really looking forward to getting this bottled and conditioning so I can drink it! I just wanted to post all of this here, because I love the recipe discussions on the JBK forum and this beer is directly the result of that (even if my recipe is not quite accurate or authentic). Thanks everyone!

Hooky Haymaker v1

For 10 L in fermentor, BIAB.

Treated mash tun water (tap water) with ~3 g gypsum and ~1 g calcium chloride. All water (~14 L) was treated with a Campden tablet.

Mashed in 9.5 L @ 66°C for 2 hours. Dunk sparged in 4.5 L @ ~69°C for 15 minutes.

About 12 L in boil kettle, 60 minute boil.

OG: 1.052 (Actual OG: 1.053)

FG: 1.014 (Actual FG: 1.012)

ABV: 5% (Calc. ABV: 5.4%)

Atten.: 72% (Actual att.: 77%)

IBU: 40 (Calc. IBUs: 44–46%)

GRAIN BILL (kg)

1.95 91.1% Maris Otter

0.11 5.1% Carapils (1.7–2.4°L)

0.08 3.7% acidulated malt

Total

2.14 100.0%

HOP SCHEDULE (pellets, in grammes)

12 @ 60 min. Challenger (7.8% AA)

8 @ 30 min. Challenger (7.8% AA)

5.5 @ 30 min. Fuggle (5.3% AA)

30 @ 5 min. Styrian Golding Celeia (2.6% AA)

YEAST

WY1318 London Ale III, pitched @ 22°C, fermented ~18°C for 5 days then allowed to rise to 23°C for ten days (so far).

The Wyeast 1318 harvested from a previous batch, kept in fridge under its beer. Made a 400 mL ‘shaken not stirred’ starter, which had been going for 24 hours by the time I pitched it into the Hooky Haymaker. Pitched into ~22°C wort, then moved carboy to a water bath and kept it between 17 and 19°C for about five and a half days, then moved it to a dark closet. The beer has hovered around 22–23°C thereafter.

It's been in the primary for fifteen days now and took a gravity reading this morning (1.012 SG). I’m really pleased with how it tastes so far. The hydrometer sample’s initial taste had some lovely citrus lemon notes and a subtle bitterness that blends with a slight malt and ester finish. Beer is light but also smooth feeling rather than thin (it’s obviously uncarbonated at this point).

I’m really looking forward to getting this bottled and conditioning so I can drink it! I just wanted to post all of this here, because I love the recipe discussions on the JBK forum and this beer is directly the result of that (even if my recipe is not quite accurate or authentic). Thanks everyone!